Who had “banking crisis” on their 2023 Bingo card?

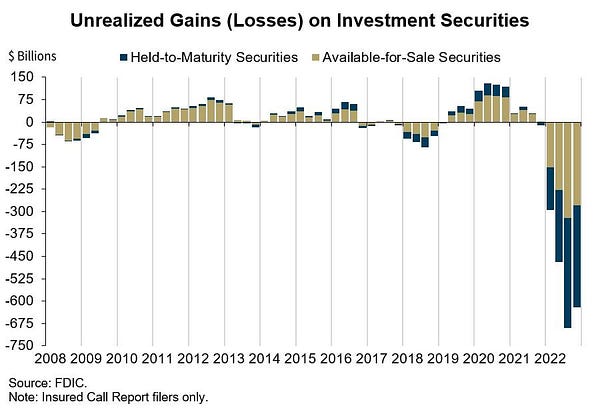

Note that every now and then the U.S. banking system is semi-insolvent, but matters work out because “on paper” losses do not have to be either realized or reported as such. Remember the 1980s?

Tyler was in graduate school in the 1980s. I was at the Fed and subsequently at Freddie Mac. Our perspectives on that period differ.

Matters did not work out. They got much worse, and at the end of the decade the taxpayers had to fork over a sizable bailout for the Savings and Loan industry (S&Ls). The moral of that story is that you should have banks mark their portfolios to market sooner, rather than later, so that they can be shut down before they take any more risks at taxpayers’ expense.

When interest rates go up, the value of a portfolio of fixed-rate bonds or mortgages goes down. Roughly speaking, if the bank paid $100 to buy a long-term bond with an interest rate of 2-1/2%, and now the interest rate on a comparable bond is 5%, the bank’s bond is worth about $50.

The regulators should make you mark down the value of your assets to their current market value and force you to shore up your capital. They should make you stop paying dividends and executive bonuses, for one thing. You should not be allowed to make any more risky loans, because of the moral hazard: if the risk pays off, you return to profitability; if it goes badly, then the taxpayers take a bigger hit via the deposit insurance fund. You have an incentive to take desperate gambles.

If the bank is genuinely solvent on a mark-to-market basis, then any gambles it takes are with the shareholders’ money. Once it is insolvent on a mark-to-market basis (or “semi-insolvent” as Tyler put it), it is taking gambles with the deposit insurance fund’s money.

But instead of requiring banks to mark long-term bonds to market value, the regulators give banks a loophole. They say that if you have your bond in a “held to maturity” account, which means you do not intend to sell it, you can pretend that it is still worth $100.

Indeed, it is true that when the bond matures, say, in twenty years, you will get your $100 in principal. But in the meantime, the interest rate that you pay to depositors will have gone up. If you have to pay 4-1/2 percent interest and you get 2-1/2 percent interest on your bond , then you lose $2 per year. For twenty years. You will run out of capital and be busted before the bond matures. When people can see that coming, there will be a run on your bank, and you will be busted right away.

The “held to maturity” loophole blinds regulators to the true condition of the bank. It allows the bank to keep taking in short-term funds, with which it can then try desperate gambles where the losses are borne by the deposit insurance fund. That is what the S&Ls did back in the 1980s. It did not end well.

Coincidentally, my latest book review essay is quite relevant. I wrote about Niall Ferguson’s The Cash Nexus, from which I took away the following.

In government or banking, mortality can be fatal

Banks lean on government, and government leans on banks

Government regulation and monetary policy, whatever its stated purpose, serves to allocate credit to the government’s preferred uses, especially its own spending

Each of these observations apply to Silicon Valley Bank.

“Mortality can be fatal” means that if you are a bank, or a government, and too many people think that you are about to die, you’re dead. If you think that your bank is insolvent, and you are not covered by deposit insurance, you run on the bank. If enough people rush to withdraw funds, the bank dies. If you think your government regime is about to fall, you don’t worry about disobeying the government, as a citizen or as a soldier. If enough people disobey the government, the regime dies.

Banks lean on government to convince people that they are immortal. Deposit insurance makes your deposits immortal. Government leans on banks to convince people that it is immortal. If government can always fund itself, then its soldiers have an incentive to remain loyal.

In the United States, deposit insurance only protects “small depositors,” meaning deposits of up to $250,000. Many of Silicon Valley Bank’s customers had larger deposits, which were not fully covered by deposit insurance. That made it particularly susceptible to a bank run.

Why did Silicon Valley Bank load up on long-term government bonds and mortgages, which lost more than a quarter of their market value over the past year? Because government regulations classified those assets as risk-free, requiring no capital to support them. And government permitted the “held to maturity” fiction that enabled banks to postpone revealing the holes in their balance sheets. Why did government regulations permit those things? I say it is because it served the purpose of allocating credit toward government’s preferred uses, which include mortgage lending and financing government debt.

My essay is long. It turns out to be timely.

Thanks to Clayton Fox for the pointer to the tweet reproduced above.

@

If the FED had to mark to market its portfolio than the government would know who to bail out. Instead they are allowed an accounting practice that is simply ridiculous. Not only, by raising rates recklessly they are doing a mistake in an attempt to correct a previous mistake, I.e. their inaction in 2021. So bottom line much of the causes are related to out of control fiscal and monetary policies conducted in Washington. Management of banks is definitively adding to the problem.

Valuing securities at historical cost vs fair value is a question of GAAP rules/standards. Couldn't regulators require banks to report securities at fair value in their call reports or TFRs or whatever they call them these days? The banks most likely know what the market value is of the securities they hold. I don't think it's a huge burden for them to write it down and include it in a big report they have to fill out, anyway. Seems like if regulators are "blinded" it's because they prefer it that way.